Loss Landscape

In this post I want to talk about loss landscapes. Loss landscapes of neural networks are high-dimensional and non-convex, which makes them difficult to study. However, in my view, understanding loss landscapes could contain the key to developing more generalizable neural networks. Luckily for me, there is still a lot of work to be done in this research area, because it has not received enough attention by the machine learning community in the past, which leaves space for eager research students to jump in. There has however already been some positive development in the area in recent years, caused by the publication of some papers that tried to connect the shape of minima with their generalization capacity [1,2,3].

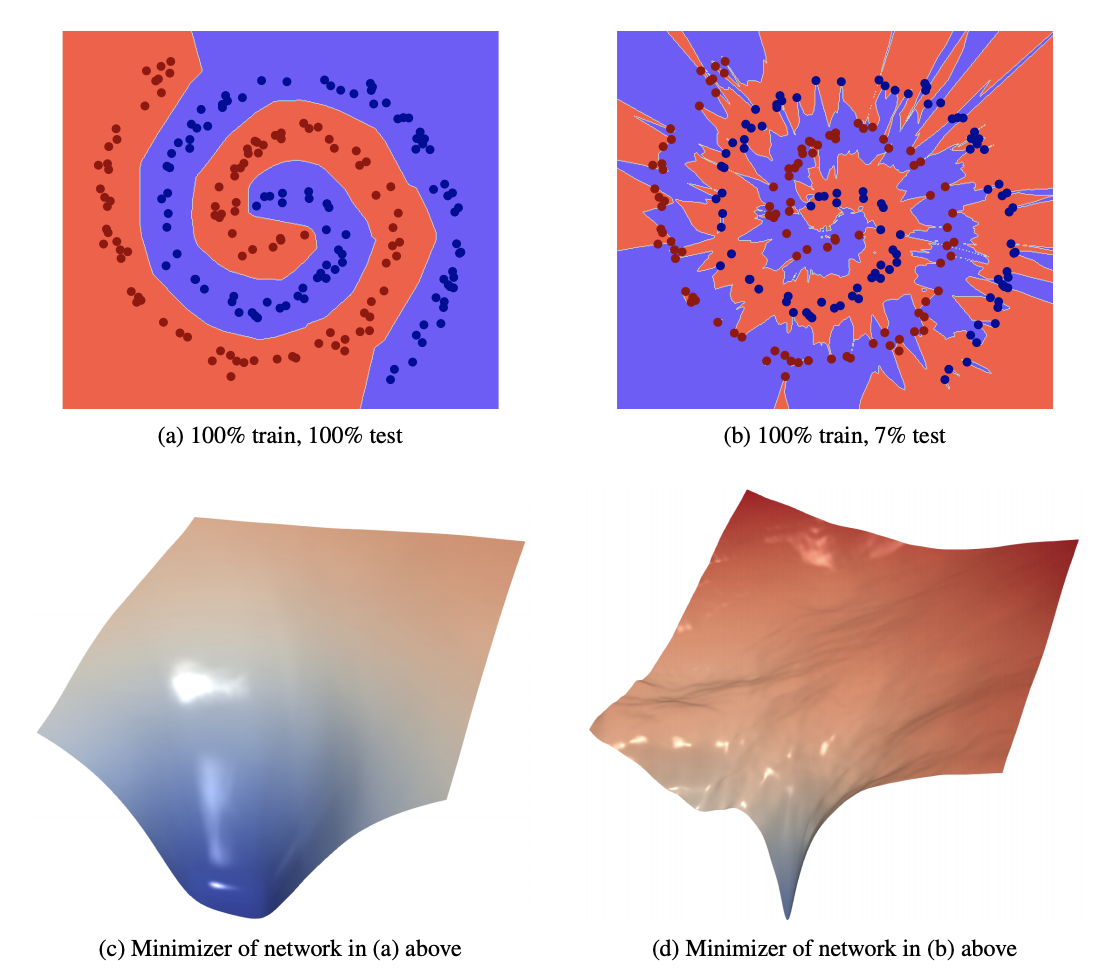

Figure adapted from [4]

Figure adapted from [4]

The intuition of these papers is that flatter minima are thought to be more robust to small changes in the parameters and are therefore more generalizable. Additionally, flatter minima have lower description lengths (i.e., less precision is necessary to describe flatter minima, because moving slightly away from a flat minima doesn’t result in much error), which is favorable according to the minimum description length (MDL) principle. Flatness is however not a scale-invariant measure, which has lead to some discussion about what it actually means to label certain minima as “flat” [5]. Despite this ongoing discussion, these papers still succeeded in bringing the study of loss landscapes into the spotlight and since then some excellent papers were published on visualizing loss landscapes of neural networks [6, 7]. In this post I hope to summarize some of the most important papers in this research area.

One may ask why a simple optimizer as SGD (stochastic gradient descent) has proven to be so successful in optimizing neural networks, despite the non-convexity of the objective functions. One would expect that optimizers are likely to get stuck in isolated local minima. It is important to realise that intuitions we may have from low-dimensional landscapes often do not translate to the high-dimensional case: critical points with high error are exponentially like to be saddle points, rather than local minima [9]. Additionally, our traditional notion of isolated basins is likely to be incorrect, because studies of the Hessian have shown that as optimization progresses there is an abundance of flat directions, with the large majority of the eigenvalues being (close to) zero [10, 11].

Other papers deal with the fact that one can almost always constrain optimization to a low-dimensional subspace of the full parameter space and still obtain good solutions [12,13]. The dimension of this subspace is referred to as the “intrinsic dimension” of the problem. The intrinsic dimension remains the same even if the size of the original neural network is increased. This seems to imply that once there are enough parameters to solve the problem, the function of any additional parameters is to make it easier for us to find a good solution. Hence overparameterized neural networks typically have better performances.

On the topic of visualizing the loss landscape - I want to highlight the paper by Fort and Jastrzebski [6]. They model a D-dimensional loss surface as the union of so-called wedges, which are interconnected high-dimensional manifolds. Different wedges are thought to correspond to different sets of functions and different initializations of the neural network will lead to minima on different wedges. Between these different sets of minima there exist low-loss subspaces that connect them. This allows movement from one wedge to another (this was also argued by [14, 15] for pairs of minima). Higher learning rates, smaller batch sizes and stronger regularization strengths, are all thought to affect the path that the optimizer (SGD) travels, because they affect to curvature of the exploration region resulting in an increased distance between an optimum and a high loss area.

References

[1] N.S. Keskar, D. Mudigere, J. Nocedal, M. Smelyanskiy, and P.T.P. Tang. On large batch training for deep learning: Generalization gap and sharp minima. ICLR, 2017.

[2] P. Chaudhari, A. Choromanska, S. Soatto, Y. LeCun, C. Baldassi, C. Borgs, J. Chayes, L. Sagun, and R. Zecchina. Entropy-SGD: Biasing gradient descent into wide valleys. ICLR, 2017.

[3] S. Hochreiter and J. Schmidhuber. Flat minima. Neural Computation, 9(1):1–42, 1997

[4] W.R. Huang, Z. Emam, M. Goldblum, L. Fowl, J.K. Terry, F. Huang, and T. Goldstein. Understanding Generalization through Visualizations. arXiv: 1906.03291, 2019.

[5] L. Dinh, R. Pascanu, S. Bengio, and Y. Bengio. Sharp minima can generalize for deep nets. ICML, 2017.

[6] H. Li, Z. Xu, G. Taylor, C. Studer, and T. Goldstein. Visualizing the loss landscape of neural nets. NIPS, pages 6389–6399, 2018.

[7] S. Fort and S. Jastrzebski. Large scale structure of neural network loss landscapes. arXiv: 1906.04724, ICML, 2019.

[8] I.J. Goodfellow, O. Vinyals, and A.M. Saxe. Qualitatively characterizing neural network optimization problems. ICLR, 2015.

[9] Y. Dauphin, R. Pascanu, C. Gülcèhre, K. Cho, S. Ganguli, and Y. Bengio. Identifying and attacking the saddle point problem in high-dimensional non-convex optimization. NIPS, 2014.

[10] L. Sagun, L. Bottou, and Y. LeCun. Singularity of the hessian in deep learning. ICLR, 2017.

[11] L. Sagun, U. Evci, U. Güney, Y. Dauphin, and L. Bottou. Empirical analysis of the hessian of over-parametrized neural networks. ICLR, 2018.

[12] C. Li, H. Farkhoor, R. Liu, and J. Yosinski. Measuring the intrinsic dimension of objective landscapes. arXiv:1804.08838, 2018.

[13] S. Fort and A. Scherlis. The goldilocks zone: Towards better understanding of neural network loss landscapes. arXiv:1807.02581, 2018.

[14] F. Draxler, K. Veschgini, M. Salmhofer, and F. A. Hamprecht. Essentially no barriers in neural network energy landscape. arXiv:1803.00885, 2018.

[15] T. Garipov, P. Izmailov, D. Podoprikhin, D. P. Vetrov, and A. G. Wilson. Loss surfaces, mode connectivity, and fast ensembling of DNNs. NIPS, 31:8789–8798, 2018.